Healthcare equity in Pakistan: Observations from a summer visit

by Aisha Khan

BSc Health Studies candidate, Western University

Wed, 22 Sep 2021

This summer, I had the chance to visit Pakistan after 8 years. Both my parents were born and raised there and had only come to Canada a year before I was born. Growing up with both of these nationalities, I spent a lot of my childhood in Karachi, Pakistan. From the climate to the infrastructure, I was always left stunned by how different life in Karachi is from the life I am familiar with, in Canada. This visit, as I returned to my motherland as a university student in a health sciences program, I couldn’t help but observe the state of healthcare and health equity in Karachi.

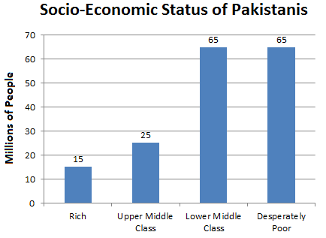

For background, Pakistan is a relatively new country having gained independence from the British in 1947. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population exceeding 225.2 million people. The population of Karachi is estimated to be around 16.1 million in 2020, making it the most populous city in the country. Pakistan is considered a less economically developed country (LEDC) with a growing economy. The following graph provides an overview of the socio-economic status of Pakistanis.

source: https://www.dawn.com/news/842873/need-for-a-new-paradigm

Pakistan is ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse. Its economy is growing and it’s home to rich cultures. It is also important to note that Pakistan still struggles with many challenges, including poverty, illiteracy, gender inequality, corruption, and terrorism. The COVID-19 global pandemic created an environment that worsened these already grievous conditions and the people at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy are sadly impacted the most.

Around the world, COVID-19 revealed the faults in our already faulty public health care systems. Similarly, Pakistan’s poor public health care system was exposed as a result of this global pandemic. When covid cases decrease, everything (including non-essential places) opens but closes at 6 pm. I was once at a bazaar and at closing time, I heard a store owner say “Run! Run! Corona only comes after 6 pm!”. Everyone chuckled. The concept of lockdown where only essential services are open is only applicable on Fridays and Sundays. However, mosques are not included. Mosques are always open with no social distancing whatsoever. I was so shocked to see how masks and social distancing are not being enforced nor emphasized. However, a full lockdown is the luxury of a government or an individual that is rich. Those in and around the poverty line are most vulnerable to COVID-19 but it is those very people that need to go out, work, and make a living of under $2.00 USD to survive. Working from home is a luxury. Clean water is a luxury. Yet even the richest in Pakistan deal with water shortages and electricity issues.

As a child, I used to visit Pakistan often. However, every trip, I became very sick and would always be admitted into the hospital, unfortunately. History repeated itself this time as well. Illness occurs due to a variety of reasons. Someone travelling from Canada, such as myself, experiences many changes including atmosphere, water, weather, food, etc. Healthcare in Pakistan is privatized. I observed this during the course of my illness. Since my family comes from an upper-middle-class background, we were able to afford my treatment and the various medications I needed. I noticed a parallel between America’s privatized healthcare and Pakistan’s, wherein those that have money are not only safe; their wealth allows them to thrive while most are left to try and survive the week. It’s America with a lower line of poverty. Most will point to the socio-economic conditions of Pakistan that make health care inequitable. However, we know that vulnerability increases with intersections of oppressive axes.

Therefore, a discussion on intersectionality is essential. Studying healthcare inequity makes it significant for us to understand the crossroads of various experiences as not all people experience the world in the same way. Intersectionality is “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things” (Crenshaw 2017). Intersectionality is really important when it comes to seeking mental health care.

Due to societal expectations like machismo, men have a hard time opening up and expressing their feelings being told from childhood that they “have to man up” and “girls cry, boys don’t”. Men with real mental health issues and illnesses can be denied treatment and in a country like Pakistan that is so deeply rooted in a patriarchal system, this is a major issue. Whereas, on the other hand, their female counterparts are viewed as ‘delicate’ and ‘fragile and are more readily able to receive help.

Intersectionality, therefore, can create a hierarchy, as more axes or intersections can lead to greater experiences of oppression. When it comes to health care services, the intersectionality of various aspects of one’s identity plays an important role in the type of care one receives but also services they seek out as well as what is available to them. Culture, societal beliefs, and stereotypes allow the creation of a hierarchy based on intersectionality. The more axes or intersections that a person identifies with can lead to greater experiences of oppression. Race, ethnicity, culture, disability, sexuality, etc. are all important considerations. I will highlight my observations of the role of gender in health inequity for the remainder of this piece.

Interestingly, when it comes to mental health and illnesses, men with depression can struggle to find medication. An uncle of mine that lives with depression regularly takes antidepressants. If his medication runs out, he needs a prescription to buy even over-the-counter antidepressants but medical stores and pharmacies give the same medication to women without the need of a prescription. Why? Depression and mental illness as a whole, is seen through a gendered lens and considered a ‘woman’s illness’. As a result of COVID-19, the need for a prescription becomes an issue for men like my uncle because many people are avoiding doctors and hospitals in fear of contracting COVID-19 from other patients. People who are even the slightest bit well-off can afford clinics and health care services where proper measures and precautions against COVID-19 are being taken. On the spectrum of poverty, though, very few people have the opportunity to be treated in such facilities. Moreover, antidepressant prices also skyrocketed during the pandemic with more people seeking help from them. And lastly, unfortunately, societal expectations force men to try to maintain their masculine image and gendered double standards make it even more difficult to reach out for help. Gender identity compounded with race, low-to-middle income, disability, etc only creates more intersections of vulnerability and oppression when one seeks out mental health care as well. With these circumstances, many are fearful to seek help. Therefore, so many barriers are created and it's the people that need help the most that suffer. At the end of the day, a family member that identifies as female is able to get my uncle the medications he needs--he never asks though, someone offers and he’ll reluctantly accept. When no one is available though, his hands are tied and his mental health struggles without the medication.

In 2018, according to the Thomson Reuters Foundation (TRF), Pakistan was ranked as the sixth most dangerous country for women (only the top 10 dangerous countries were listed with number 10 being the US, interestingly enough). TRF’s survey mentioned six key areas to rank countries that are least safe for females including healthcare, discrimination, cultural traditions, sexual violence, non-sexual violence, and human trafficking. Not only is the gender gap extremely apparent in Pakistan, the mere experience of living in Pakistan as a woman is frightful and dangerous to one’s life. There are economic, educational, legal, political, cultural and so many more types of disparity between men and women in Pakistan. In terms of healthcare utilization, men continue to play a decision-making role in women's access to healthcare including in times of emergency (Shaikh et al. 2005). There are many cultural and religious barriers that also include restricting women's mobility if they are unaccompanied by men (Mumtaz et al. 2005). Domestic violence as a form of discipline is also widespread and many women and children are victims of abuse, and prone to trauma and mental health issues. Ali et al. found that in urban Karachi, “the violence women have to face contributes to the development of multiple forms of psychological stress and serious mental health problems” (2011). The restrictive life circumstances for women seriously inhibit the much-needed women’s empowerment in Pakistan. Better health care services and reliable health surveillance systems are required to serve women that are victims of abuse. The presence of these are slowly increasing but more needs to be done to fill in this health inequity gap as a result of gender.

Sources

Kimberlé Crenshaw ON Intersectionality, more than two decades later. Columbia Law School. (n.d.). https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later.

Mumtaz, Z., & Salway, S. (2005). ‘I never Go Anywhere’: Extricating the links between WOMEN'S mobility and uptake of reproductive health services in Pakistan. Social Science & Medicine, 60(8), 1751–1765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.019

Pakistan population growth Rate 1950-2021. MacroTrends. (n.d.). https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/PAK/pakistan/population-growth-rate.

Pakistan ranked sixth most dangerous country for women. Daily Times. (2018, June 28). https://dailytimes.com.pk/259389/pakistan-ranked-sixth-most-dangerous-country-for-women/.

Shaikh, B. T., & Hatcher, J. (2005). Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. Journal of public health, 27(1), 49-54.

Ali, T. S., Mogren, I., & Krantz, G. (2013). Intimate partner violence and mental health effects: A population-based study among married women in Karachi, Pakistan. International journal of behavioral medicine, 20(1), 131-139.

Photo by Muneer ahmed ok on Unsplash