Climate Change Adaptation & Mitigation: Vulnerability and Health

by Aisha Khan

BSc Health Studies candidate, Western University

Wed, 29 Sep 2021

One winter, many years ago, I remember someone was brushing off the snow on their car windows when they exclaimed “What? There is no such thing as global warming! Just look around!”. At the time, I was in the sixth grade and I knew there was something wrong with that statement, but I had to find out more. I was standing in my school library when I decided that global warming would be the topic of my science project, mainly because I had a few encounters with people who didn’t think it was real--what made this so unreal? I had no idea that that 12 year old girl would learn so much global warming and consequently, climate change over the course of the next few years. And I also had no idea how dire our situation is, and as a whole how vulnerable we are.

Carbon dioxide, a driving force behind global warming, lingers in the atmosphere for hundreds of years and Earth takes a while to respond to warming. Even if we managed to stop emitting all greenhouse gases today, climate change would still affect our future generations. In this way, global warming is in our future, and we are stuck with it (NASA 2021). We can deal with climate change through two approaches, climate change mitigation and adaptation. Climate change adaptation means adapting to the future or current climate. The goal is to minimize our vulnerabilities to the harmful effects of climate change. Adaptation focuses on reducing negative effects by taking advantage of small opportunities which arise. Climate change mitigation means trying to minimize the emissions of harmful greenhouse gases, and limit the long-term effects of global warming (GEF 2018). The most important and most impactful way of mitigating climate change is through substituting the use of coal, oil, gas, and other fossil fuels with cleaner energy sources such as electricity or solar power (IRENA 2019). Other ways of mitigation can be attained through changes in our waste management, agricultural industries, and forest preservation (IPCC 2007). Reducing cattle and meat consumption can assist this mitigation because both are closely linked with the production of methane gases. These gases have a very high, short term impact and although it releases the least amount of carbon dioxide during combustion than any other hydrocarbon, it releases the most amount of heat from any organic molecule. These “diminishments” can also take place in political and economical communities through emission pricing models such as carbon taxes, and divestment from fossil fuel finance. Climate change mitigation aims to attack the source of the problem so it does not become a life-changing problem in the future.

Whilst mitigation is focused on tackling the causes, adaptation is focused on reducing negative effects through taking advantage of opportunities which arise. It is important to recognize that our focus cannot simply be on one approach, however, Laukkonen et al. write that mitigation and adaptation “do not always complement each other, but can be counterproductive” (2009). Therefore, priorities need to be set, in order to avoid conflicts. To solve our climate crisis, there is no right or wrong approach, rather the most sustainable outcomes can be achieved with a productive blend of both (Laukkonen et al, 2009).

‘Vulnerability’, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is “the degree to which geophysical, biological and socio-economic systems are susceptible to, and unable to cope with adverse impacts of climate change” (IPCC, 2007). Individuals and communities’ vulnerability to climate change is determined by many factors and it is not only limited to the location of their settlements. The approach that we take to deal with climate change is very important as certain attitudes reflect on the services local governments provide and how effective and capable those services are as well as the extent to which the society, as a whole, is able to cope with climate change impacts (Laukkonen et al, 2009). Most consider poor communities in less economically developed countries to be the most vulnerable to climate change as basic urban services such as water, sanitation, drainage, energy, and transport, etc, are unavailable to them. They are at an extreme disadvantage since climate change creates additional problems for them. Poverty creates a state of heightened vulnerability that requires comprehensive strategies and approaches that combine climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts (Laukkonen et al, 2009). The health impacts of climate change will vary from population to population as well as individual to individual due to differential exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity of individuals and groups (Paavola, 2017).

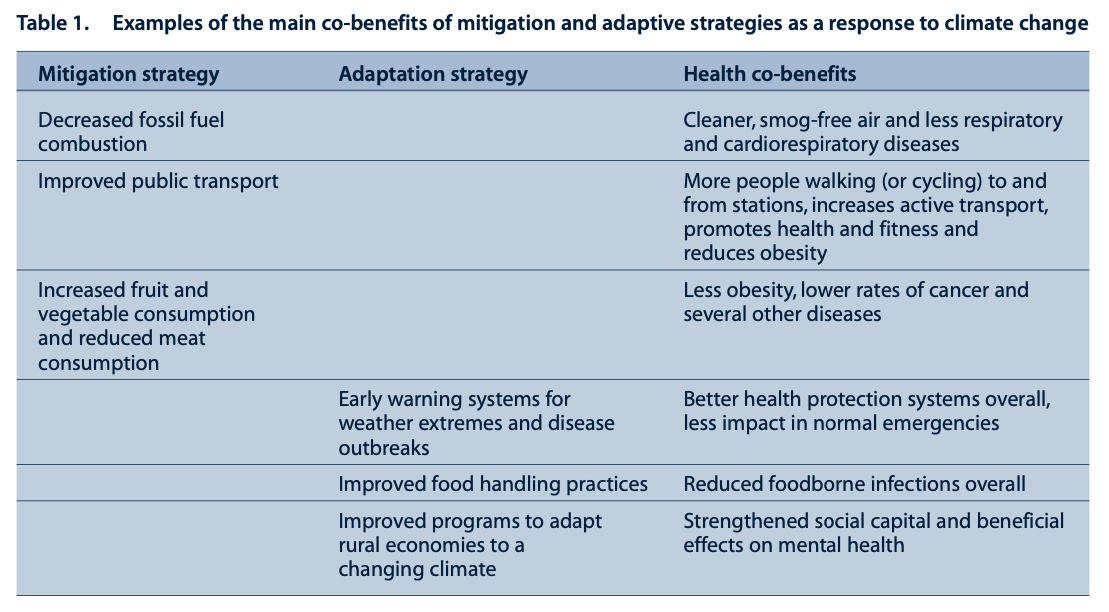

Furthermore, interestingly, mitigation and adaptation strategies also create co-benefits for individual health and community health. Non-climate-related health hazard exposures are reduced and health promotion behaviours and lifestyles allow this to happen (Kjellstrom et al, 2009). The following table provides a summary of health co-benefit examples that arise from climate change responses as a result of mitigation and adaptation approaches.

Ultimately, we must think about those affected the most by climate change and then work towards making sure they are not left behind struggling. This can be done through a combination of mitigation and adaptation strategies. As opposed to worsening individual and community health as a result of climate change, mitigation and adaptation approaches will have increasing health co-benefits. Unfortunately, the people in positions of power must take a stand for our climate and mitigation and adaptation strategies should be prioritized. When CEOS, politicians, and other important stakeholders truly understand the alarming situation we are in, they should take concrete steps to ensure the survival of a healthy world. We need to close this knowledge gap. In addition, it is not enough for our national and state/provincial public health agencies to take responsibility for interventions. Individuals within their communities must also take part in helping to reduce climate change–related morbidity and mortality.

Sources

Climate change mitigation. Global Environment Facility. (2020, September 24). https://www.thegef.org/topics/climate-change-mitigation.

Corporativa, I. (n.d.). Adapting to climate change: What will the earth look like in 2030? Iberdrola. https://www.iberdrola.com/environment/climate-change-mitigation-and-adaptation.

Falling renewable power costs open door to greater climate ambition. Falling Renewable Power Costs Open Door to Greater Climate Ambition. (n.d.). https://www.irena.org/newsroom/pressreleases/2019/May/Falling-Renewable-Power-Costs-Open-Door-to-Greater-Climate-Ambition.

Kjellstrom, T., & Weaver, H. J. (2009). Climate change and health: impacts, vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation. New South Wales public health bulletin, 20(2), 5-9.

Laukkonen, J., Blanco, P. K., Lenhart, J., Keiner, M., Cavric, B., & Kinuthia-Njenga, C. (2009). Combining climate change adaptation and mitigation measures at the local level. Habitat international, 33(3), 287-292.

NASA. (2020, September 18). Climate change adaptation and mitigation. NASA. https://climate.nasa.gov/solutions/adaptation-mitigation/.

Paavola, J. (2017). Health impacts of climate change and health and social inequalities in the UK. Environmental Health, 16(1), 61-68.

Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K. B., ... & Miller, H. L. (2007). Summary for policymakers. Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1-18.